6. Interacting with a computer (in a Nutshell)

Nowadays, most interactions with the operating system (the “conductor of the orchestra” of the programs installed on your computer) are achieved by clicking on icons that represents programs or data files. When you click on a program, you start it; when you click on a document, you open it within its associated program.

The is convenient but limited. Imagine you could “talk” to your computer and ask it: “Slave ! find all the jpg graphics files in this folder, make copy that you reduce to size 512x512 pixels, and place them in a new folder”. This is actually possible, by typing a single line in a Terminal running the bash shell:

mkdir thumbnails; for f in *.jpg; do convert "$f" -resize 512x512 thumbnails/"${f%.jpg}-512x512.jpg"; done

6.1. The shell

Inside the terminal, you are interacting with a program which runs an infinite loop where it prints a ‘prompt’, wait for you to type some instructions and, when you press the Enter or Return Key, interprets the line and execute the instructions.

This program is called a Shell. Various Shells exist: bash, zsh, poweshell. they speak slightly different languages.

There even is a shell that speaks python: it is called ipython (for interactive python).

One difficulty is that you need to know the language of the shell and, also, the available programs on your computer. By contrast with Graphical User Interfaces that display Windows/Icons/Menus, Textual shells have a poor ergonomy in that there is no visual way of discovering the potential actions. Yet, because they are languages providing variables, loops, … shells facilitate the automation of tasks.

For example, to create 20 directories in a single bash command under linux:

for f in 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10; do mkdir -p subject_$f/data subject_$f/results; done

The good news is: in these lectures, you will need to use only three shell commands:

* cd (change directory)

* ls (list)

* pwd (path of working directory).

I recommend that you read the web page at http://linuxcommand.org/lc3_lts0020.php which provides very clear explanations.

You do not have to learn more about the shell for these lecture, but learning more about it may be good idea in the long run.

6.1.1. Why learn the command shell?

“To properly understand the role of a shell, it’s necessary to visualize what a computer does for you. Basically, a computer is a tool; in order to use that tool, you must tell it what to do—or give it “commands.” These commands take many forms, such as clicking with a mouse on certain parts of the screen. But that is only one form of command input.

By far the most versatile way to express what you want the computer to do is by using an abbreviated language called script. In script, instead of telling the computer, “list my files, please”, one writes a standard abbreviated command word—‘ls’. Typing ‘ls’ in a command shell is a script way of telling the computer to list your files.1

The real flexibility of this approach is apparent only when you realize that there are many, many different ways to list files. Perhaps you want them sorted by name, sorted by date, in reverse order, or grouped by type. Most graphical browsers have simple ways to express this. But what about showing only a few files, or only files that meet a certain criteria? In very complex and specific situations, the request becomes too difficult to express using a mouse or pointing device. It is just these kinds of requests that are easily solved using a command shell.

For example, what if you want to list every Word file on your hard drive, larger than 100 kilobytes in size, and which hasn’t been looked at in over six months? That is a good candidate list for deletion, when you go to clean up your hard drive. But have you ever tried asking your computer for such a list? There is no way to do it! At least, not without using a command shell.

The role of a command shell is to give you more control over what your computer does for you. Not everyone needs this amount of control, and it does come at a cost: Learning the necessary script commands to express what you want done. A complicated query, such as the example above, takes time to learn. But if you find yourself using your computer frequently enough, it is more than worthwhile in the long run. Any tool you use often deserves the time spent learning to master it.”

(Extracted from Emacs’ eshell documentation)

To learn more about how to control the computer by interacting with the shell, I can only highly recommend two resources:

6.2. Disks, Directories and files

Most computers (not all) have two kinds of memories:

volatile, fast, memory, which is cleared when the computer is switched off (processor’s caches, RAM)

‘permanent’, slow, memory, which is not erased when the computer is switched off (DISKS, Flashdrives (=solid-state drives))

The unit of storage is the file.

Files are nothing but blobs of bits stored “sequentially” on disks.

A first file could be stored between location 234 and 256, a second file could be stored at location 456 on your disk.

6.3. filenames, directory structure

To access a file, one would need to know its location on the disk. To simplify human users’ life, the OS provide a system of “pointers”, that is filenames , organised in directories.

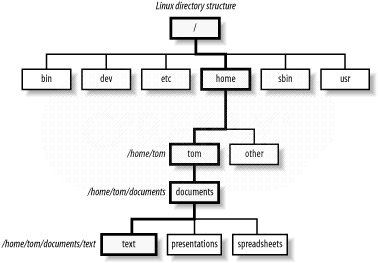

To help users further, the directories are organised in a hierarchical structure: a directory can contain filenames and other (sub)directories. The top-level directory is called the root.

Linux directory structure

To locate a file, you must know:

its location in the directory structure

its basename

See absolute or relative pathnames

Remark: a given file can have several names in the same or various directories (remember: a filename is nothing but a link between a human readable charachter string to a location on the disk)

6.4. Working directory. Absolute pathnames vs. relative pathnames (..)

It would be tedious to always have to specify the full path of a files (that is, the list of all subdirs from the root)

Here comes the notion of working directory: A running program has a working directory and filenames can specified relative to this directory.

Suppose you want to access the file pointed to by /users/pallier/documents/thesis.pdf. If the current working directory is /users/pallier, you can just use documents/thesis.pdf (notice the absence of ‘/’ at the beginning).

To determine the current working directory in a shell, list its content, and change it:

under bash (or ipython):

pwd ls cd Documents

6.5. What is the PATH?

A command can simply consists of a program’s name: typing it and pressing Enter will start the program.

The shell knows where to look for programs thanks to an environment variable called PATH.

The PATH variable lists all the directories that contains programs. Try the following commands:

echo $PATH

which ls

which python

Under bash, to add new directories to the PATH:

export PATH="newdirectory":"$PATH"

For example, under Git Bash for Windows, to be able to start sublime text from the command line, by just typing subl, you must add its folder to the PATH, as follows:

export PATH="/c/Program Files/SublimeText 3/":"$PATH"

To make this setting permanent, you must copy this line within a file .bash_profile in your home directory.

6.6. What is a library (or module/package)?

A library is a set of new functions that extend a language.

Libraries can be used simultaneously by several processes.

E.g. the function @@sqrt@@ can be defined once, and called by several programs.

In Python, one uses import to be able to access functions from a library (a.k.a. module), for example:

import math

math.srqt(2)